Rates for ships carrying commodities that fuel global industries and keep the world fed have soared, raising hopes of a turnaround in fortunes for the embattled dry bulk shipping sector.

Roaring Chinese demand for iron ore, a key steel ingredient, a return to strength for manufacturing in the rest of the world and under-investment in new vessels in recent years have powered a sharp increase in prices for dry bulk carriers, which transport unpackaged raw materials in large holds.

The Baltic Dry index, which tracks rates for the three largest classes of ships, has risen to its highest level in more than a decade, soaring over 700 per cent since April 2020. Capesize vessels, the largest type with an average capacity of 180,000 deadweight tonnes, are fetching $41,500 a day for immediate hire, close to double of a month ago and almost eight times last year’s average, according to Clarksons Platou Securities. “China’s insatiable appetite for iron ore has been the single most important factor,” said Ulrik Uhrenfeldt Andersen, chief executive of Golden Ocean, the largest listed owner of capesize ships.

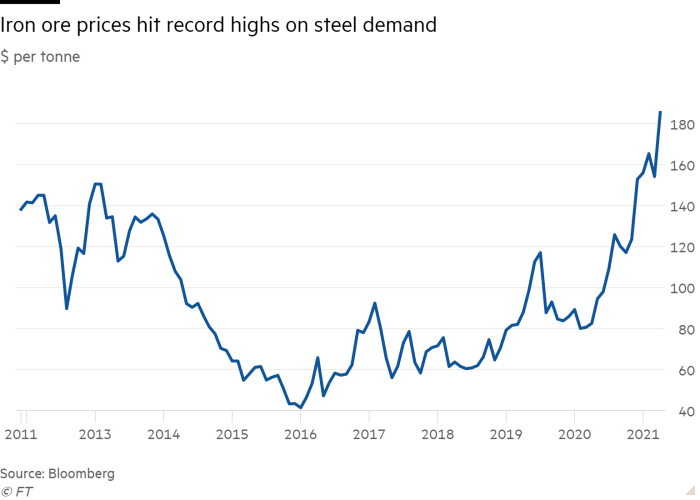

Iron ore, a crucial source of profits for some of the world’s biggest miners, hit a record high of almost $230 a tonne this week as Chinese steel mills cranked up production to make the most of high domestic prices. This followed the introduction of production curbs in Tangshan, China’s top steelmaking city, as part of a pollution crackdown. However, the move only served to reduce capacity and push up domestic prices, which mills in other parts of the country have seized on.

A host of other factors have contributed to squeezing the shipping market, from record high US coarse grain exports to the trade dispute between China and Australia, which has tied up vessels with coal and other materials outside the ports of the world’s biggest commodity importer. “The stars are aligned for dry bulk,” said Lasse Kristoffesen, chief executive of Norwegian carrier Torvald Klaveness.

The sector has been plagued by an overcapacity of ships since the 2008-9 financial crisis, despite robust demand growth for raw materials. The pandemic-induced drop in commodity markets last year piled on the misery, but now soaring demand for raw materials as the world recovers has helped transform dry bulk’s fortunes. “For all big commodity shipping, it has been a lost decade,” said Kristofessen. “It has been a depressed market and returns have not been sufficient, largely due to the fact that we were ordering vessels like there was no tomorrow. It has taken 10 years to wash that out of the system.”

The industry is confident that prices will keep rising this year. Petter Haugen, an analyst at Kepler Cheuvreux, said it is possible that capesize vessels will fetch $100,000 a day in the second half of the year. Analysts cited fiscal policies to stimulate economic growth, the clamour to refill depleted inventories and the muted supply of new vessels as supporting higher prices.

But the industry is divided on whether the rally will solidify into a longer lasting trend. Soaring prices for a broad set of commodity markets has prompted talk of a supercycle — a prolonged period of high prices — as large economies fire on all cylinders. That has set off speculation as to whether there will be a trickle-down effect for dry bulk shipping.

Joakim Hannisdahl, head of research at Cleaves Securities, said that a long period of price growth was looking more likely with each month that owners hold off buying lots of new vessels. “As long as we don’t get a new ‘black swan’ on the demand side then this could be one supercycle people will remember for a lifetime,” he said, referring to unexpected events with large impact such as the pandemic.

An uptick in container shipping markets from autumn last year, which preceded the rally for dry bulk vessels, spurred a wave of orders for shipyards, delaying the delivery date for any bulk vessels ordered now.

“Yards are filling up fast with orders for non-bulkers,” said Edward Buttery, chief executive of Taylor Maritime, an owner of small carriers. His company is preparing for a rare maritime London listing as institutional investor interest in shipping is rekindled.

Some owners are hopeful of further tailwinds, pointing to global regulation under debate that could force ships to slow steam to reduce carbon emissions from 2023, which would constrain fleet availability. “Another catalyst is that by 2023 new regulations on ship designs and emissions are expected to be introduced.

Approximately 75 per cent of the dry fleet would not be compliant with the new regulations,” said Andersen. But sceptics said the key missing ingredient for a supercycle is the lack of a sustaining force like the rise of China, which drove the last period of high prices, and whose imports now make up almost half of the dry bulk shipping market.

Environmental pressures are also bearing down. If China is serious about cutting emissions and reducing steel output, analysts believe restrictions like those in Tangshan will need to be rolled out in other regions.

The outlook appears even bleaker for coal used in power generation, which accounts for almost 20 per cent of seaborne dry bulk shipments. “This decade will have thermal coal in decline,” said Peter Sand, chief shipping analyst at shipowner trade body Bimco. “There are more obstacles on the horizon when talking about climate change and dry bulk shipping.”

He added that prices — still only at roughly a third of 2007 levels — would likely ease off since there is still a surplus of vessel capacity. “I do see this as a rare off season event . . . there are underlying factors that define a certain level of gravity,” he said. But he added “what’s not to like right now about dry bulk shipping”.